Jason Todd, Ph.D., Xavier University of Louisiana

One of my favorite professors in college was a guy named Harry Cargas. I attended a small liberal arts school in St. Louis called Webster University. Harry was a bit of a superstar, both on campus and around the world. He'd written numerous books about the Holocaust. He was good friends with Elie Wiesel, Kurt Vonnegut, and Václav Havel. He was an incredibly nice guy, accessible and easy to talk to, even for a shy first-year student. I took way too many Harry Cargas classes -- Holocaust Literature; Utopias and Dystopias; The Novels of Kurt Vonnegut. Eventually, my advisor told me I couldn't minor in Harry Cargas.

But he was also a bit of a stereotype. Although he bore a striking resemblance to Paolo Freire, he embodied the very thing Paolo Freire criticized in Pedagogy of the Oppressed when he spoke of the Banking Concept of Education. At Webster, most of the English classes met in a building called Pearson House, which was actually a house donated by some people named Pearson that was used for classrooms and offices. All of Harry's classes were in the evenings, once a week, 4:00-8:00, taught in the Pearson's former living room. Harry sat at a desk on the dais in front of the fireplace. Every week, we would read a different novel and then listen to Harry up there on his dais talk about his thoughts on the novel. He was, quite literally, the Sage on the Stage, sharing his knowledge with his students.

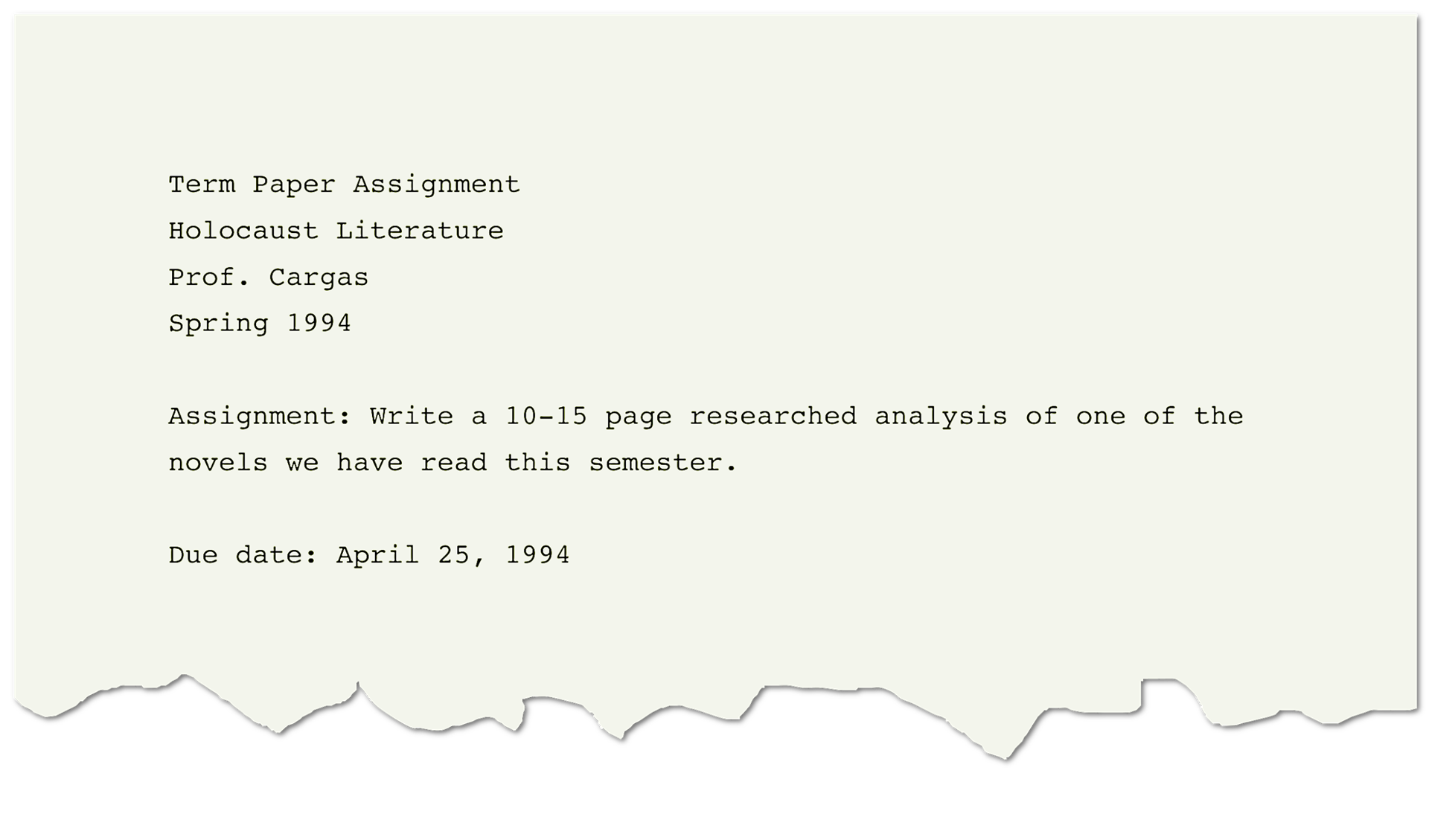

What's all this have to do with writing assignments, you might be asking? Harry used writing the way a lot of faculty use writing: as a means of summative assessment, as a way to see if the students have learned what they were supposed to learn. I did some digging through my files recently, and found one of his old assignment sheets.

This is an extreme example, I know, but one worth considering when we assign writing to our students. We need to ask ourselves what it is we are hoping to accomplish with the assignment. Is this it? Are we just assigning a paper to see if they've learned enough from our class? If so, why a writing assignment? Why not just a multiple-choice test? Or, are we hoping to do more? Are we challenging them to more deeply explore a topic that was brought up in class? Are we hoping to see them flex their critical thinking muscles by making connections between what was read, what was discussed, and what they've found through their own research? Are we evaluating their ability to do that research? Are we assessing how well they can express complex ideas through the dialect of academic writing? Are we, possibly, trying to get our students to establish a connection between their real lives and this strange world of academia in which they find themselves?

All these things, I'd argue, are possible through writing assignments (although perhaps not all at once), but not if we simply tell the students to write something, which is what Harry used to tell us to do.

A few years ago, three faculty members from three very different institutions decided to see if they could figure out what made writing assignments "meaningful" to their students. By thinking in terms of meaningfulness, these researchers were looking for assignments that weren't simply "useful" or "enjoyable," but that had some kind of lasting impact on the students (Eodice, Geller, & Lerner, 2017b). Ultimately, the researchers identified several key findings as to what made a writing assignment meaningful to students:

● They are unique/different from other writing assignments.

● They enable the students to integrate their personal interests.

● They allow students to explore course content more thoroughly.

● They give students some freedom to approach the assignment in their

own unique way (Eodice, Geller, & Lerner, 2017a).

At the same time, researchers at the University of Nevada - Las Vegas were investigating how any academic assignment could be made more accessible and understandable to students. This research, led by Mary-Ann Winkelmes, identified the need for greater "transparency" in the way we make our assignments. According to Winkelmes, by specifically explaining the purpose for an assignment, by clearly explaining the steps we expect the student to take in order to complete the assignment, and by thoroughly describing how we will evaluate the final product, we make it much more likely that students, especially first-generation and under-prepared students, will succeed with those assignments (Winkelmes, 2014).

By blending these two novel concepts -- meaningfulness and transparency -- we can design writing assignments that will not only more accurately demonstrate what our students have learned, but will also challenge our students to do their best, most engaged work. As an example, let's think about what Harry's assignment might have looked like had he had access to this recent research. For brevity's sake, I'll just think about the purpose statement here.

Purpose: The purpose of this assignment is to challenge you to apply your understanding of the conventions of Holocaust literature by analyzing a specific work within that genre. While we have discussed each of the assigned texts in class, we have only skimmed the surface of each. This assignment will enable you to dive deeply into one of them, while also demonstrating your ability to do literary research and to integrate that research into your writing. Finally, this assignment will also give you the opportunity to flex your writing muscles by engaging as an equal with some of the best Holocaust writers and scholars.

The purpose statement is a critical component of transparent assignments. Instead of simply saying, "Do this because I'm telling you to do this," you're saying, "Here's why I want you to do this." But it's also a great opportunity for you to justify the meaningfulness of the assignment. I'm asking students to make a personal connection with one of the novels (and giving them the opportunity to choose that novel). Notice some of the language here: the students are being challenged and enabled, as well as being given a great opportunity. But I'm also explaining the real purpose of the assignment: analysis, research, and writing. By writing this statement out, I'm giving my students a sense of what exactly I'm looking for with this assignment, but I'm also spelling out for myself (and them) how I will be evaluating the assignment. Once students know what's expected of them, they can start thinking about how to make their final product unique to them.

I loved Harry as a professor, and after my second or third class with him, I knew how to write a paper for him that would get me an A, but I don't remember what any of those papers were about. And while I can't ensure that every one of my students will feel this way, I want to do my best to make sure my teaching and my assignments have a lasting impact on them. By applying the findings from the researchers behind The Meaningful Writing Project and Transparency in Learning and Teaching, I think I'm closer to achieving that goal.

References

Eodice, M., Geller, A. E., & Lerner, N. (2017a). Findings. Retrieved August 6, 2019, from http://meaningfulwritingproject.net/?page_id=50

Eodice, M., Geller, A. E., & Lerner, N. (2017b). The Meaningful Writing Project Learning, Teaching and Writing in Higher Education. Norman, UT: Utah State University Press.

Winkelmes, M. (2014). TILT Higher Ed Examples and Resources. Retrieved August 6, 2019, from https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources

Jason Todd studied writing with Frederick and Steven Barthelme and Mary Robison at the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi. His fiction has appeared in journals such as Southern California Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, Fiction Weekly, and 971 Magazine. Since 2007, he has been a member of Department of English at Xavier, where he teaches American Literature, Freshman Composition, Modern English Grammars, and The Graphic Novel and Social Justice. From 2007 to 2010, he served as Xavier's Writing Center Director. From 2010 until 2015, he served as QEP Director, managing Xavier's Read Today, Lead Tomorrow initiative. In 2015, he became the Center for the Advancement of Teaching and Faculty Development's first Associate Director for Programming. As Associate Director for Programming, Dr. Todd assists in providing high-quality, relevant, evidence-based programming in support of CAT+FD's mission to serve faculty across all career stages and areas of professional responsibility.