Carolyn Stallard, Ph.D. Student, The Graduate Center, CUNY

This past October, I had the privilege of volunteering for and presenting at the 9th Annual Pedagogy Day held at the Graduate Center CUNY and organized by members of the GSTA. At first I was concerned; would my non-psychology-focused presentation go over well at a conference hosted by the Psych department? The conference was open to anyone, but as a music educator would I benefit from the presentations?

As the proceedings began, it was immediately evident that my concerns were for naught; from the start I could see that this was a conference of great benefit to anyone interested not only in psychology but also in higher education pedagogy in general. I truly feel as if I learned something useful from every presentation I attended. In particular, I loved the message of keynote speaker Sue Frantz (click here to see a recording of the keynote address), who challenged the audience, when preparing to teach an Intro Psych course for undergraduates, to consider what their real-life neighbors might need to know about psychology. Though the topic at hand was purely psychology, I found the question to be relevant to any course taught to students who are not planning to major in a particular subject. When teaching an introductory course, it is important for educators to remember that the students enrolled will someday be our neighbors –construction workers, educators, dentists, pilots – so what do they need to know about the subject being taught?

My contribution to Pedagogy Day was a bit different than Sue Frantz’s. Rather than challenge the audience to think about what non-majors might need to know, I challenged them to think more creatively about the collection and retrieval of information, particularly to encourage/improve research and critical thinking skills. I shared information on a mod – a modification of a pre-existing game – called Superfight by Jack Dire. In the original version of this self-described “game of absurd arguments,” players draw three each of two kinds of cards: Characters and Attributes. For instance, a player may have a hand containing three characters – Abraham Lincoln, Superman, and Godzilla – and three attributes – the ability to shrink in size, a water gun, and a beard full of bees. Each player then chooses a character and an attribute from their hand and “battles” through debate against another player to determine who would emerge victorious in a fight. A third player judges the debate and decides who wins.

Figure 1. Example of the original Superfight game by Jack Dire

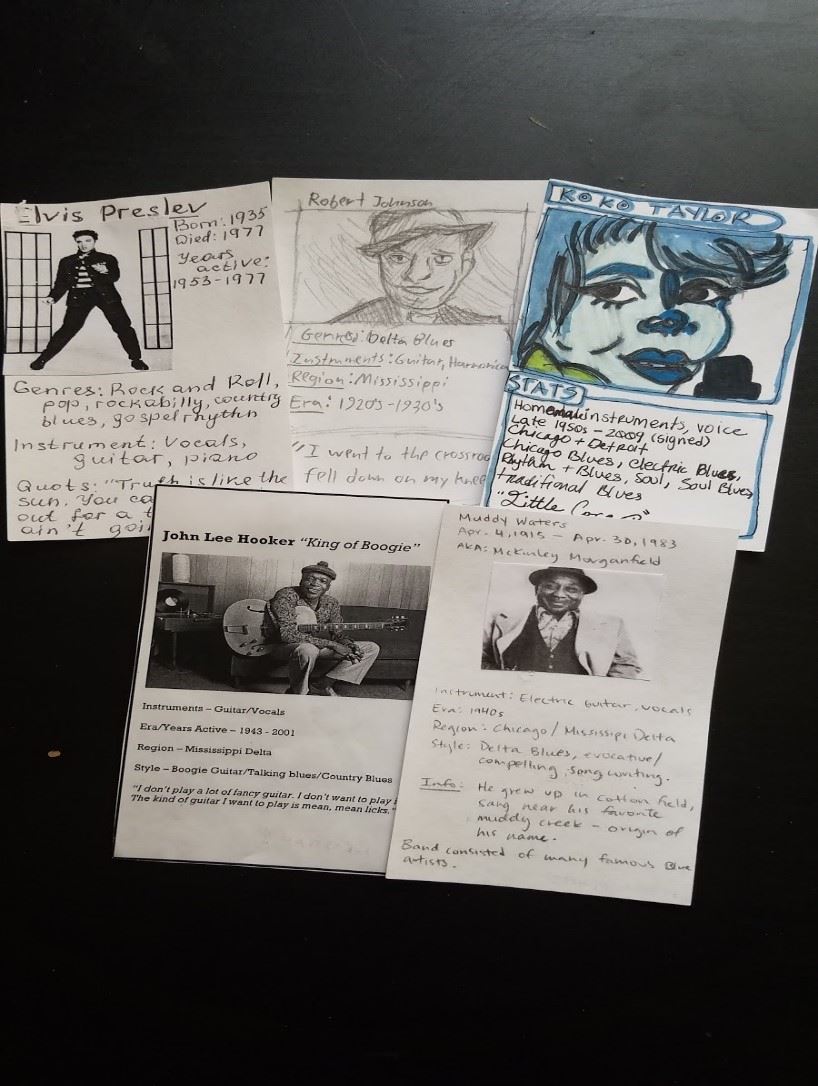

My version, called Music Melee, takes this debate concept and the accompanying game mechanic of randomization and applies it to music history. In the basic version, character cards contain information about a significant musician we’ve studied in class, and attribute cards are instruments. Students form groups of three (two to actively debate, one to judge), choose an artist and instrument from their hand, and make an argument for why their choice would outperform their opponent in a battle of the bands.

Figure 2. Example of Superfight cards created by students

To make the game run smoothly in my 50-student class, after each of the initial three players in a group has battled each other (creating a “best two out of three” scenario) the two losing players join the winner as support, resulting in a new team of three. This pod of three then finds two other pods to debate (with a larger arsenal of characters to choose from now) and again, the two losing pods join the winner, creating teams of nine. This continues until there are three massive teams debating in the room. At this time, for the final round, only the team champion (the single person on the team who has yet to lose any debate) can speak for their team in a live debate in front of the class.

This game is useful for a number of reasons:

- Students create the cards. In the week(s) leading up to the game, each student must choose a couple of artists to research. Thus, the students themselves create the playing deck, requiring very little preparation from the instructor. I give the students a number of specific points they must include on their cards, treating each as a small research project, but another professor might adjust this in a different way.

- It encourages not only information retrieval, but also critical thinking. Often, the instrument/musician pairings are not ideal; the best combo a student might produce from their randomized hand might be, for instance, Umm Kuthum with a didgeridoo. In this situation, students must get creative in their arguments, not only recalling information learned in class but also considering what factors might create a persuasive argument (in this example, a student might argue that because Umm Kulthum is considered such an important vocalist in Egypt and the broader Middle East, she may have the lung power to master a didgeridoo better than say, Jimi Hendrix, who did not play any aerophone instruments).

- Students learn what does or does not make a strong argument, which can later be applied to research papers. In my class, we spend time before the game having a full class discussion to determine what does or does not make a strong argument. We create a sort of rubric on the board, which students can then refer to when making or judging an argument during gameplay.

- The game can be easily modified to up the ante. For instance, you may add in random situations/scenarios mid-debate: Suddenly the musicians are performing in 18th century Venice or can only perform acoustically; how does this affect the argument being made?

- Likewise, the game can be modified to teach a number of different subjects. At Pedagogy Day I asked the audience for ideas, and a number of instructors mentioned the idea of creating a deck of psychologists as the character cards, with various research variables/items (B.F. Skinner’s rats could be a card, for instance) as the attributes.

My interest in games as a tool for learning has led me to become involved in the CUNY Games Network. As part of the steering committee for the CUNY Games Network, I firmly believe that game-based learning is a useful method for teaching any subject in higher education. Music Melee is a simple game, but whenever I introduce it in class the students latch on; I am always surprised when students who have been quiet all semester suddenly come alive during their debates.

This is just one example of game-based learning (GBL) and “modding.” To learn more, I highly encourage anyone interested to take advantage of the plethora of resources and fellow pedagogues interested in GBL in higher education here at CUNY. The CUNY Games Network is open to anyone (CUNY or non-CUNY, as long as your interest is GBL in higher education), and we welcome those with previous GBL experience as well as those just starting out. To sign up for the mailing list and read more about games in the classroom, visit cunygames.org. There, you will also find information about the upcoming CUNY Games Conference 5.0, which will be held January 18, 2019 at Borough of Manhattan Community College (click “Events” to find the conference info.).

Carolyn Stallard is an Ethnomusicology student and Senior Teaching Fellow at the Graduate Center and an adjunct instructor at Brooklyn College. She is a member of the steering committee for the CUNY Games Network and researches game-based learning in higher education.