By Naomi J. Aldrich, PhD, Assistant Professor, Grand Valley State University; Developmental Psychology program at the Graduate Center, CUNY Alum

I have found that one of the most boredom-inducing topics to cover when teaching Introductory Psychology or Child Development is the information on neuropsychology. Over the years, I have tried different ways to cover the material without overwhelming my students or putting them to sleep and have been mostly unsuccessful. However, I think that I have finally found a way to achieve better student understanding and interaction…Zombies!

Several months ago, I came across a wonderful book The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse by Steven C. Schlozman, M.D. (2012). The book is written from the perspective of a neuroscientist who is keeping a journal of his investigation of the causes of zombiism in hopes to find a cure before the world is overrun with the ravenous undead. The book takes the reader through the different stages of the illness (i.e., Ataxic Neurodegenerative Satiety Deficiency Syndrome, ANSD) and in doing so, emphasizes what makes the zombie brain so different from ours. This is what made me so excited, I felt like I acquired a better understanding of the brain myself by learning about what makes zombies tick, so I did some more research. What I found is that a large number of people have started to teach children about the brain by using this zombie model. Given pop-culture’s focus on zombie’s today I believe this may be a great way to engage our undergraduates.

This summer I taught a class of 7- to 13-year-olds and their grandparents about the brain using information from this book and it was one of the best classes I have ever taught! I am now planning to incorporate this for all of my neuropsychology undergraduate lectures from now on.

Here are some main points:

1) Zombie Stagger:

- Normal people can walk around with good coordination between their body & brain.

- Zombies stagger around and seem clumsy. They bump into things and often hold their arms out for balance.

- Why? Deficient cerebellum

2) Zombie Appetite:

- Typically after we eat we get full. We have a varied diet, but we do not eat humans.

- Zombies are always hungry, even after a huge meal. They also like eating humans, which is a problem.

- Why? Defective hypothalamus

3) Zombie Rage:

- Regular people get angry and there are some situations where they may even feel rage. However, most people feel anger and then return to their normal emotional state.

- Zombies are aggressive at all times. They are extremely violent and tend to attack humans in an enraged state. They are dangerous and cannot be reasoned with.

- Why? Enlarged amygdala

4) Zombie Stupidity:

- Humans are able to solve problems, talk to each other, and make decisions. These abilities make us unique and have contributed to our success as a species.

- Zombies are known for their stupidity. They often can’t figure out how to open doors and rarely, if ever, plan ahead. They are terrible problem solvers and seem to lack any ability to communicate except through grunts.

- Why? Inadequate Frontal Lobe processing

Here are links for lesson plans (including PowerPoint slides) for teaching the Zombie brain. These were developed for grades 7 to 12, but can be easily adapted for use with undergraduates (created by Katie Gould & Dr. Steven Schlozman). I have only used the first two lessons, but depending on your class you may want to incorporate information from all four:

Zombie Autopsies Lesson 1: You’ll be Wishin’ for some Neurotransmission and Background Story

- This lesson introduces students to neurons and neurotransmission through multi-media and active learning games.

Zombie Autopsies Lesson 2: The Neuroanatomy of a Zombie

- This lesson teaches students about neurotransmitters, neurotransmission and neuroanatomy through multi-media and active learning games.

Zombie Autopsies Lesson 3: Super Spooky Psychiatric Medicine to Save the World

- This lesson introduces students to the concept of medications development and gives students a simulation to apply what they know about neurotransmitters, neurotransmission and zombies.

Zombie Autopsies Lesson Plan 4: Publish or Perish…for Real

- This lesson introduces students to writing an academic journal article and allows them to apply what they have learned during the Neuroscience and Zombies Unit.

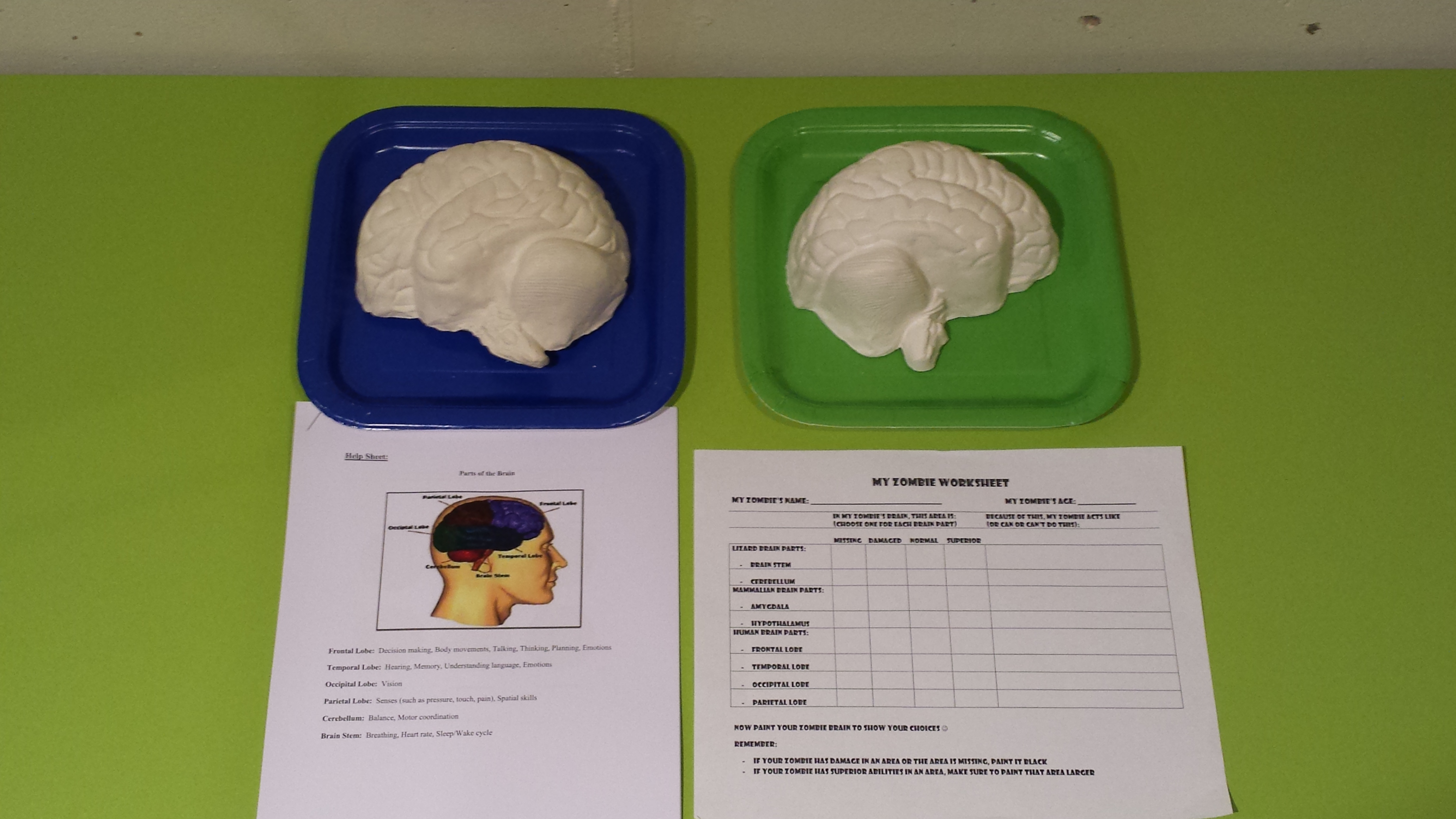

Here is the lesson plan I created for the class with 7- to 13-year-olds. My goal was to make it more interactive and fun. Basically, I first presented the children with information about how the normal human brain functions and then had them conduct a series of mini-experiments in which they had to figure out what lobe of their brain was responsible. Then they identified the lobe of the brain by painting a plaster-of-paris model of the left hemisphere. Next, I presented information about how zombie brains are different from ours and had them design their own zombie and they painted the lobes of their zombie brain (the right hemisphere with black paint indicating a deficient lobe). Finally, they had their grandparent come to the front of the class and demonstrate how their zombie would behave based on what they chose.

Zombie Brains – Session Outline

1. Introduction

a. Welcome and thank you for helping us explore the human brain through zombie behavior at GVSU. Today we will talk about how the human brain influences our behaviors and abilities so you will be ready to learn about the brains of zombies. As almost all behavior can be traced back to the brain, scientists believe that zombies have damaged or diseased parts of their brain. If we can figure out what parts have been affected by the disease, then there may be hope that YOU will be able to develop medicine that can cure them if real zombies ever came to exist.

b. Warm up (ask the campers & write answers on board):

i. How does a zombie look different from a human?

ii. How do they behave differently than humans?

2. Present “Normal” Brain information

3. “Normal” Brain Activity

a. Pass out “Brain Tests” packet to each pair & help them get started

b. While they are working, pass out “Your Brain” model, paints, etc.

c. Discuss their brains and test results

4. Present “Zombie” Brain information – try to relate information back to lists on board

5. “Zombie” Brain Activity

a. Pass out “My Zombie” worksheets

b. While they are working, pass out “My Zombie Brain” model, paints, etc.

c. Once finished, each pair should come up & explain choices with grandparent acting as zombie

Even if you choose not to use the Zombie model in your classroom, I would highly recommend the book itself… you will learn a lot, although it’s not for the squeamish J