By Laura Freberg, Ph.D., California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo

Choosing the right materials to support your course is one of the most important decisions an instructor must make. Whether you choose your own materials independently, serve on a textbook decision committee, or administer a course for which materials are chosen for you, this decision will have significant implications for the quality of the course experience for you and your students.

Today’s instructors face a bewildering array of choices, which has both an upside and a downside. On the positive side, having many choices is always a good thing, as courseware can be tailored to a specific group of students with characteristics best understood by their professor. On the downside, reviewing the many available materials represents a significant commitment in instructors’ time, which is already in very short supply.

The point of this article, then, is to help instructors focus on some of the key variables involved in courseware decisions. In the interest of transparency, I am actively authoring two traditional textbooks for Cengage as well as serving as lead author for a lower-cost electronic textbook for TopHat. I have also worked with the APS Wikipedia Initiative and even sat on a panel for APA on “Teaching Without Textbooks.” While I fully appreciate the success of open source software, the typical model for open education resources (OER), I am also willing to pay for outstanding proprietary products like those from Adobe. The point is to obtain the tools that best fit your needs.

Pros and Cons

Each type of courseware has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. By examining these, we can begin to identify areas where the materials differ.

The Traditional Textbook

The traditional textbook provides the complete package. Not only do you get a heavily peer-reviewed document, which minimizes errors, but publishers generally provide testbanks, instructors’ manuals (e.g., lecture notes, activities, lists of TED talks and videos), online homework and enrichment activities, and PowerPoints. This option is literally “Doc in a Box.” The textbooks are also updated at regular intervals. This might not be essential in algebra, but it’s a must in sciences like psychology.

On the negative side is the elephant in the room—cost. Many people do not know why the costs of traditional textbooks are high, which contributes to the mentally lazy vilification of traditional publishers as “evil corporations.” The actual printing cost of a book is relatively little. Most of the cost represents work by a fairly large group of people, not just the authors. We have development editors who help shape our content, copyeditors, photo researchers, indexers, and sales teams. Hundreds of paid peer reviewers scour our work for errors. Still others produce the testbanks and other ancillaries, which are also reviewed. The publisher must ensure that online materials present a positive user experience, leading to an ever-increasing need for expensive IT people and equipment. Traditional publishers are held to a very high standard of accessibility and ADA compliance, which is also expensive.

Publishers of both textbooks and books for the general public face these same challenges. What makes life much harder for textbook publishers is the impact of the used book and rental markets. Who sells or rents their copy of Harry Potter? Sacrilege! The relatively tiny printing cost is the only variable that depends on the number of books produced. The remaining costs that I mention must be paid regardless of how many books are sold. If you spread these costs over single payers (each reader of Harry Potter or an assigned textbook), traditional textbooks would be as affordable as Harry. This doesn’t happen, of course, as the vast majority of students assigned a textbook will purchase used or rental copies. In spite of “don’t sell” notices adorning instructors’ desk copies, some instructors sell them anyway for extra spending money. Amazon affiliates and the campus bookstores are the main recipients of this largesse. They pay the student very little at buyback, store the book on the shelf for a few days, then sell it again at nearly new prices. None of this money, of course, goes back to the publisher to offset any production costs. What makes the traditional textbook expensive is the fact that new book sales represent a relatively small fraction of overall users.

![]()

Image : The upper graph demonstrates the effects of the used book market on publisher sales and the lower graph demonstrates the effects of both the rental and used book market over the six semester lifespan of a textbook (Benson-Armer, Sarakatsannis, & Wee, 2014). Publishers only recoup production costs from new sales, not total use of their intellectual property. 1 = Assumes percentage of students who do not acquire textbooks shifts from 20% to 8% due to introduction of the rental market (which reaches 30% penetration).

Just as the music industry did to avoid the hemorrhage that was Napster, publishers have moved to electronic versions of textbooks, or the iTunes model. The advantage to the publisher is not due to lower printing costs, which are quite small anyway, but rather to the spreading of production costs across more users because resale is limited. Electronic books are typically half or less of the cost of the print version and will go lower as adoption of electronic books increases. Incidentally, the idea that students learn better from print than electronic books appears to be a myth, at least according to careful research presented by Regan Gurung (2017). For students who insist on something they can hold in their hands, publishers make loose-leaf versions available for a few extra dollars over the electronic book cost.

Electronic materials have another advantage. Many students do not buy their assigned text. When instructors use electronic books and their associated homework, they know exactly who does and does not purchase a textbook. The analytics associated with the electronic books even show you how much time each student spends with the materials, which can be very helpful when advising a student doing poorly in your class.

We still don’t know how well the revolutionary Cengage Unlimited model is going to work. This model (nicknamed the Netflix model) allows students access to ALL Cengage titles while paying a slightly higher fee than they would for a single electronic title. Students rarely pay attention to the publishers of their assigned textbooks, but this model might make them more sensitive to that. If successful, we can anticipate all of the major publishers will begin offering this service.

Before jumping to conclusions that students ALWAYS want low-cost or free textbooks, consider the following. Many of the lowest income students are receiving federal grants that include the purchase price of new textbooks. Washington surely doesn’t want the textbooks back at the end of the term, so the student is free to sell the books. This provides a significant income for these students, who object strenuously to OER or electronic books with no resale value. Affluent students often follow a similar strategy. Their parents pay for books but do not consider their resale value, so the student gets a bit more discretionary income without having to ask for it.

A final key aspect of the decision to use a traditional textbook is whether the instructor actually needs a textbook. If you provide students with comprehensive study guides and PowerPoints, and assess exclusively on that content, it should come as no surprise that students either do not purchase the text or complain about having to purchase the text. Texts are only valuable if they are used.

Low-Cost Textbooks

All of us receive frequent emails from indie textbook publishers, both print and electronic, that promise a less expensive option of perhaps $40 or so. These options vary substantially in quality and in the support provided for the instructor.

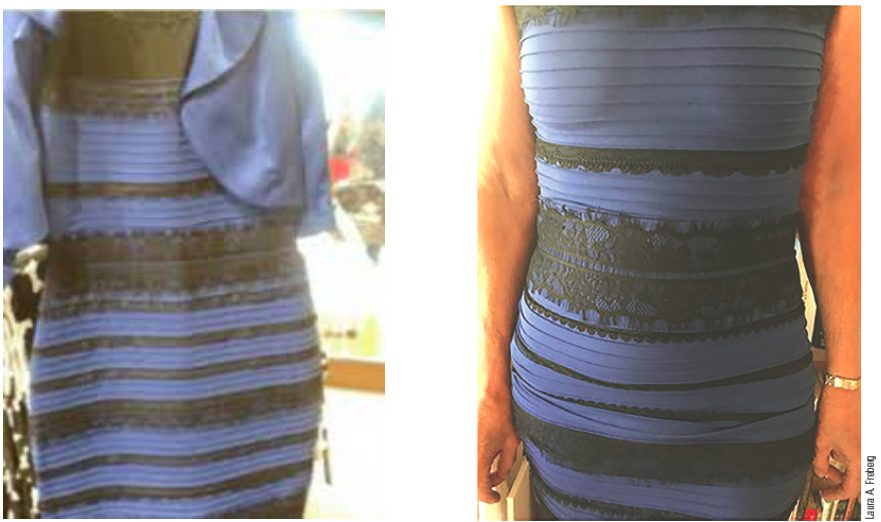

My all-electronic TopHat project probably represents the higher end of this classification in terms of quality. We have very capable development editors and were supported by a copy editor and graphics designer. Costs are cut by using photos that were open source. Photo permissions for traditional textbooks can be very pricey. I actually purchased the “blue/black or gold/white” illusion dress from eBay and wore it for a photo for my Cengage books (and yes, I can attest to the fact that it really is blue and black) when the difficulties of obtaining permission to use the original photo were insurmountable. Another cost savings was the relatively sparse pre-publication review. We had one person per chapter review our work prior to publishing compared to hundreds in traditional text publishing, which I must say made me nervous. TopHat assumes that crowdsourcing will fix problems after publication, a point of view shared by many open educational resource (OER) advocates.

![]()

![]()

Image 1 Caption: To save money, I actually purchased a version of the blue/black/white/gold dress on eBay so we could include a photo in my textbooks. The original photo is on the left and I am wearing the dress on the right. My husband, armed with his cell phone camera, and I walked around the house until we found lighting that allowed us to duplicate the illusion.

In spite of these cost savings, TopHat charges $61 for our book as opposed to the $95 cost of the basic Cengage electronic books. So even when you do not have to worry about the effects of used and rental textbooks on your sales, there is an underlying truth about the costs of producing quality materials – it can only go so low.

Open Education Resources (OER)

The largest advantage of OER is cost to the student. Who doesn’t like free stuff? Having paid for my own college education, I am not unsympathetic to this. Instructors can endear themselves to their students and administrations by using OER, resulting in higher evaluations. Their classes get special recognition in the registration process, in a not-so-subtle public shaming of instructors who prefer traditional or low-cost materials. Note that OER is not “free” at the institutional level. Colleges and universities spend considerable resources on grants and support personnel for OER that reduce support for other functions.

OER advocates tell me that cost is not the only advantage. You can bring in a multitude of materials in addition to a free text and instructors can adapt the material to fit their needs. I agree, but there’s nothing stopping you from doing these things WITH the electronic versions of traditional texts, which have the capability of embedding videos, assessments, activities, and documents seamlessly. In many cases, the publishing company staff will set up the course the way the instructor wants it.

On the downside, if traditional textbooks are “Doc in a Box,” OER materials are stone soup. It might be possible to simply use materials as-is, but I know very few people who do that. Some people enjoy the revising and curating process, but others simply can’t fit additional course prep time into a heavy research and service load. Additionally, instructors might not have the necessary skillset for these tasks. Being a great teacher and researcher does not automatically make you a courseware expert.

Continuity and updating of OER materials by entities such as OpenStax is somewhat vague. Foundation money might provide for original production costs, but who has ownership of the ongoing health of these materials?

As mentioned previously, OER materials, unlike traditional text materials, are rarely assessed for ADA compliance. You don’t have to look at too many materials before finding some with blinding areas of inaccessibility. Bringing materials into compliance is expensive and time-consuming, and lawsuits are even more so. Until now, OER materials have been given a “pass” not enjoyed by traditional publishers, but that is not likely to last forever.

Head-to-Head Comparisons

In 2017, Regan Gurung undertook direct comparisons between OER materials in introductory psychology (NOBA) and three traditional textbooks (Hockenbury & Hockenbury, Cacioppo & Freberg, and Myers & DeWall). You might have heard of numerous studies that show that students using OER have the same level of achievement as students using traditional textbooks, but Gurung carefully points out and controls for the design flaws in those efforts. He concluded that traditional textbook “users enjoyed their classes less and reported learning less than OER users but still scored higher on the quizzes.” In other words, just because students seem happier with OER does not mean they are learning more.

OER are usually presented on campus as a positive contributor to social justice. This claim might be tempered if in fact student outcomes are superior with traditional materials. If less affluent, less-prepared students are more likely to be offered materials that result in lower performance, this is actually working in the opposite direction of true equity.

Making the Decision

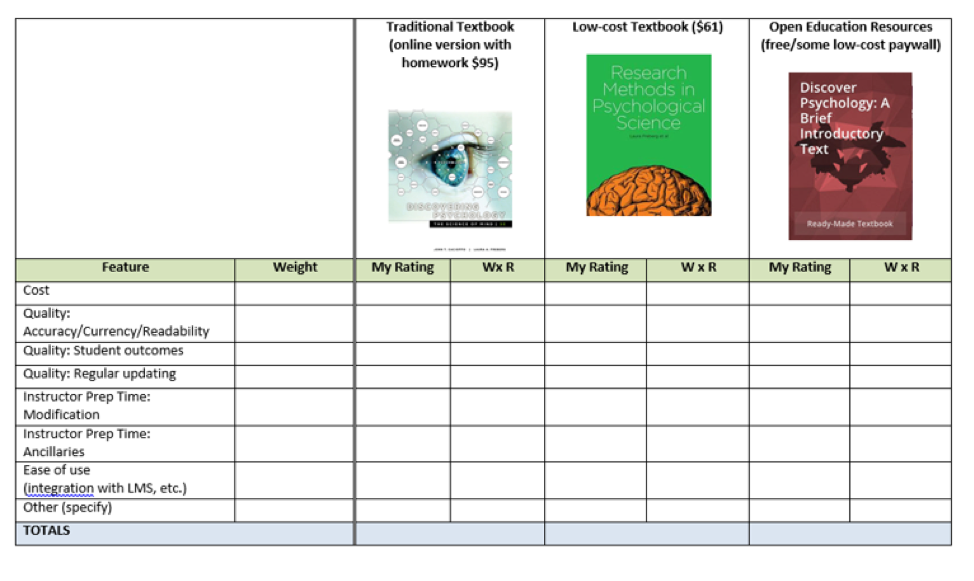

As anyone teaching heuristics knows, the human decision-making system is subject to flaws. We can possibly avoid some of those flaws by thinking more systematically. One such approach is a utility model, where we assign ratings and weights to variables of interest and let the math point us in the right direction. If you’d like to try that out, I’ve provided a model you can use or adapt to your own needs.

![]()

![]()

Begin by considering each “Feature” and assigning it a “Weight,” with “5” being “very important” and “1” being “not important at all.” Next, examine your sample materials, and assign each a “Rating,” with “5” being “very good” and “1” being “not very good.” Then, all you have to do is multiply Weight by Rating and sum the results. Ideally, this should give you an idea about which type of materials is likely to bring you the greatest level of satisfaction.

No one type of courseware is likely to meet the specific needs of all students and their instructors. As empiricists, we should be willing to experiment. If what we’re doing isn’t working, we should try other things. Ultimately, our feedback and the feedback from our students can help producers of content to develop even better materials.

References

Benson-Armer, R., Sarakatsannis, J., & Wee, K. (2014). The future of textbooks. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/the-future-of-textbooks

Gurung, R. A. R. (2017). Predicting learning: Comparing an open educational resource and standard textbooks. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 3(3), 233-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/stl0000092

Laura Freberg is a Professor of Psychology at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, and adjunct instructor for Argosy University Online. Dr. Freberg received her bachelors, masters, and Ph.D. from UCLA and conducted her dissertation research with Robert Rescorla of Yale University. She is serving as the 2018-2019 President of the Western Psychological Association.